Nihao! Hello and welcome to China! Most game developers in the mobile space are starting to branch out and look to other markets. There’s been some strong interest in China. With over a billion people and about 400 million smartphones being used in China according to IDC, most developers are drooling over the idea of making a game for the Chinese market. Consultant for the Chinese game market Luke Stapley tells more.

Many have already found success, like EA with PopCap’s Plants vs. Zombies 2, King with Candy Crush Saga, the currently trending Clash of Clans as well as all the match-3 clones. While these have continued dominance, for insight on how gaming grew in the middle kingdom it’s best to take a look at the most popular trend in China for the past decade: the MMORPG games.

Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Games have been the main staple genre for Chinese gamers. Many have been playing them for years, mostly due to not having regular access to a console or portable gaming device. The reasons for that are politics, piracy, and traditional behaviors of Chinese customers. So, the history of gaming in China can be seen as quite different from that in the West.

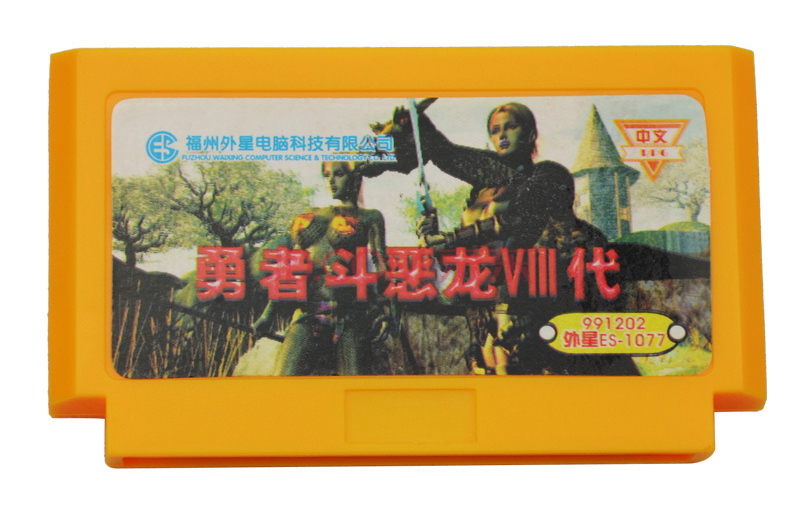

A quick summary of Chinese games history begins before 1999 when the Chinese government banned all consoles and handheld gaming as a way to curb children from not studying at school. Prior to this, most people played arcades, or were too poor for a Japanese or American console. Gamers would instead purchase knock-off Famicom systems and cartridges containing games that were hacked into Chinese.

At this time happened the rise of the phenomenon of Asian Internet Cafés. They allowed gamers to go into a shop, rent a computer for a few hours and play MMORPGs, use the internet, chat with online friends, etc. The cafés still exist today, but with the price of computers and mobile devices dropping and the increase in wages, they’re becoming more and more irrelevant.

With the lack of console and handheld gaming (excluding the iQue), Chinese and other Asian companies started creating their own PC games. MMORPGs became the most popular genre in China and grew further when Blizzard released World of Warcraft in China in 2005.

Starting from client-based subscription games, China began testing out ideas and ways to increase profit in ways that the West is just now using in the mobile market, such as freemium and over-the-phone purchases.

I’ve asked friends in the Chinese games industry to help me find the titles that helped shape the MMORPG space of China. Each game mentioned below has been innovative, and created something special for Chinese gamers, and Western game developers also can learn from it.

Fantasy Westward Journey

Created in 2003, this was the first (and some say the only one at that time) Chinese MMORPG to gain a large following in China. Made by NetEase, a search engine company like Yahoo, which also creates videogames, it was a subscription-based title.

The game is based off one of the four most famous novels in Chinese history, “Journey to the West”. The story is about a monk traveling to India, and the misfortunes and adventures surrounding his journey. The story highlights numerous folk traditions, myths and creatures that are still popular in Chinese traditions today.

The PC specs were very low, so it was easy for most internet bars to install the game on older computers, allowing for more to play in smaller rural areas. The game at its peak had over 1.5 million DAU and is currently in its second generation.

The gameplay is reminiscent to a mix of classic Japanese RPG fighters with trading, PvP modes and multiple chatrooms. Even though the graphics weren’t as high quality as those of Western MMORPGs at the time, the use of popular storylines and a developed chat room system allowed for players around China to talk to each other and helped in the growth of the genre.

Legend of Mir

Back in 2001, this game was known in China as The World Legend, a bootleg copy of a game popular in Korea. But the Chinese company of Shanda purchased controlling rights for that game in 2004 after a lengthy lawsuit with the original creators, WeMade Entertainment. It started with a subscription-based model and now has both free-to-play and subscription-based servers.

The game itself is a very simple MMORPG with very few character options to choose from: a fighter, monk, or wizard. The gameplay has very similar look to Ultima Online. The game continues to be popular in China with both sequels Legend of Mir 2 and the Legend of Mir 3 making substantial profits for WeMade and Shanda.

Like Fantasy Westward Journey, the game didn’t require much to run on a PC. It was also one of the first ones to have private servers built by players thanks to the bootleg copies being produced, forcing the original game makers to add a freemium edition to combat the copies. This trend of freemium to dissuade bootlegs and copycats has become very common after this incident.

Another large breakthrough was the opportunity to purchase in-game items. In China, players respect those who spend more money (a.k.a “Pay-to-Win”). This is very different from most Western cultures’ “Skills-to-Win” ideology. Some players have spent thousands of dollars and hours to upgrade their characters. This has brought news stories of attacks on players who steal or sell items from their avatars, and other problems not likely to be seen in the West.

MU Online

Like The Legend of Mir, MU Online (known as Miracle in China) is a Korean MMORPG. Created by WEBZEN, it was brought to the Chinese mainland in 2003. It was a subscription-based game that currently is free-to-play.

The biggest difference from other games was its use of OpenGL, allowing for better 2.5D (isometric view) gaming. This was at that time the most visually appealing MMORPG in China with a huge advancement compared to Mir or FWJ.

The visuals are based off Medieval themes with castles, kings, knights and wizards. The gameplay is very much like Diablo 2 with randomized drops, point-and-click attacking, and an inventory system. What players enjoyed most of all was the leveling system that makes it possible to go from 1 to 400 levels with a rebirth mode, allowing players to start at level 1 again with the same equipment and status, but with more powers unlocked. One Chinese developer told me about a player reaching level 1,602 within a year (3 rebirths, level 302). Respawning does require an in-game purchase.

Because the game was not directly published in China, Webzen looked for companies to operate servers for Chinese players. The company The9 was one of the first web game operators in China and became overwhelmingly successful from operating MU Online. Its work with MU Online allowed the company to purchase rights for World of Warcraft in 2005 for Chinese gamers until 2009 when Blizzard moved its servers to NetEase.

Journey aka Zhengtu

Chinese publisher Giant Interactive created the game Zhengtu in late 2004. The game is the first popular free-to-play game in China. It’s currently in its second generation.

At the time when World of Warcraft and older MMORPGs were taking over the Chinese gaming landscape, Journey is seen changing the idea that only subscription-based gaming can be popular. With a vast promo campaign in small villages and outskirts internet cafes, and a large TV campaign promoting the company (working around laws against game advertisement on TV), the game grew big enough to beat World of Warcraft with over 1,000,000 peak concurrent users.

The game itself is nothing new from a MMORPG standpoint. The king has died and you are part of one of the 10 tribes trying to inherit the kingdom. Despite the game being set in a feudal era, it has stock trading, modern clothing and cars. One feature from there that is still used in many MMORPGs is the “autofight”, allowing your character to fight and complete quests without the need to move your mouse.

Zhengtu’s popularity among the lower class with little disposable income made the game a hit. But it was the marketplace structure for purchasing items and weapons that made the game successful for the company. Through the “Pay-to-Win” model, many rich players would spend hundreds of dollars to become the best fighter. There are estimates that people would spend over 1000 rmb (about 129$ USD at the time) per month to upgrade their characters!

Though there were big gains from Zhengtu, it’s also a game full of controversy over the overpowered rich gamer against the casual gamer, the use of in-game currency for real-life money laundering, and hiring many of the designers from the Legend of Mir series out from under Shanda Games.

Dungeon Fighter Online

With so many 3D MMORPGs flooding the market in 2007 including World of Warcraft, Korean game makers Nexon took a sharp right and presented an MMORPG straight out of a beat-em-up genre. DNF looks just like a souped-up Final Fight or Golden Axe with the same look and feel of a typical Super Nintendo game. The game had a huge following in China with numbers surpassing World of Warcraft for several months.

At that time, the Chinese government asked companies to place limits on MMORPGs, since they started hearing news of marathon gaming with some people living in internet cafes and stories of infants dying because of gaming parents. The government devised a plan of forcing developers to give players dramatically lower experience and gold the longer they played. To combat this and keep gameplay fun, DNF was one of the biggest MMORPGs at the time to install a fatigue counter.

Players could only enter a certain number of dungeon rooms before their avatar was too exhausted to fight, so that gamers would have to rest. We can see games like Candy Crush Saga adopting the “fatigue” idea, with a recharge only worth some money.

The game was a huge hit in Asia with comic books and a cartoon series created based off it. DNF is still popular in China with over 3 million peak concurrent players in 2012.

Crossfire

Counter Strike has been very popular for years in Europe and America. The issue was that it was a paid game, and having home servers to play with friends would be very expensive for China. CrossFire by Korean developer Smilegate created a first-person shooter similar to CS with a free-to-play experience, adding MMORPG-like features such as chat rooms, experience points and upgrades. The game was release in 2007 with a free-to-play model.

Though very much like Counter Strike in terms of missions, weapons and graphics, the game did come with different missions that Chinese players enjoyed, such as “Ghost mode”. It allowed one team to play invisible only when standing still and only carrying knives capable of one-hit kills, while the other team used their normal gear.

The biggest reason for its popularity was Smilegate partnering with the biggest internet company in China, Tencent, as a web game operator. Tencent is the juggernaut that created QQ, an instant messaging service widely used in China as well as WeChat, a mobile messaging service. Tencent is seen as the Google of China, having its own news, email, social networking and gaming sections.

The addition of CrossFire helped gain popularity for the game and also got Tencent to benefit from its game library. Today Tencent has its own mobile games, sometimes under the name of Timi. Many of their published games are in the top 10 game lists of app markets around China.

Audition Dance Battle Online

With all these blood and guts and carnage games, you’d expect a prettier game to come along to gain the female market. Though farming games have been the trend, Audition by Korean company T3 Entertainment gained a following with their large array of music and dance moves that you could share with friends.

Players in the game would join dance rooms and make their avatar dance to hit songs in China (the game was localized to each country with their own music tastes.) The game followed the same rhythm game premise of pressing the right buttons at the right time to create combos and trying to score more points than the other dancers in the room.

Audition is special because it’s a perfect example of the Asian micro-transaction model, allowing players to spend very little money to customize their avatar, add new dance moves and new songs ($.05 - $.25). This model became popular in Korea due to the same piracy issues as in China, and continued to innovate in both Korean and Chinese markets for years to come.

The growth of games for girls and the ability to “marry” other players to achieve specific items allowed for many opportunities to test how much gamers are willing to spend on microtransactions. This has brought about a huge advancement in the way gamers spend money in games in Asia, compared to the challenges many Western companies are facing today in the mobile space.

Studying the Chinese game industry, I’m amazed to see the different levels of complexity in the pricing mechanics and unique features that are being offered to mobile games that originate from their MMORPG roots.

Sadly, old habits die hard, as many of the MMORPGs mentioned in the article are now on mobile and are eating up most of the mobile economy in China. This, however, should not scare you away from China, as many gamers are starting to wane over the repetitiveness of these games and are ready for new experiences from the outside. All in all, great games always find success, no matter where they come from.

Comments