Is there a way to offer in-app purchases in kids’ apps that’s both ethical and profitable?

Yes, if you follow these five rules . . .

Developers of mobile games and apps for kids are in a bind.

They want to harness the awesome potential of mobile computing to revolutionize children’s media, but they also want to eat. According to EEDAR, the average age of mobile gamers in North America dropped by an astonishing 20% between 2013-2014, attributable to a huge influx of young players with smartphones and tablet devices. Kids under 12 represent a huge and growing audience for game developers, yet the top grossing games in the Kids category of Apple’s App Store rarely qualify among the top 200 grossing titles in their Games category.

Much has been written about the “right” way to make money from free-to-play apps for kids. While most of the money in the App Store is made through in-app purchases (IAP), some mobile developers and commentators contend that IAP monetization in children’s apps is inherently unethical and should be avoided altogether. While monetizing through premium apps, subscription, or advertising is in many ways more straightforward, with fewer ethical pitfalls, I believe there are ways to ethically and sustainably offer in-app purchases in kids’ games if the implementation is guided by the following five principles:

1. Don’t Try to Redefine “Free.”

My five year old son was recently allowed to download a free iPad game from the App Store based on a popular preschool IP. He was very disappointed when he discovered there was no real gameplay available when he launched the app; all the “free” game allowed him to do was navigate a hub world showcasing the characters, levels, and activities that were available for purchase. A disappointed five year old is uniquely capable of transmitting unhappiness in a wide broadcast radius, and as a result I can now say with conviction that we will never download another app associated with those characters.

If your game is promoted as free to play, then it should indeed be free to PLAY — not just free to shop. The core game mechanics should actually be free. A storybook where only the first chapter is free, or a game whose free component is an environment that only serves to showcase paywalled content, isn’t really free.

2. When a Child Buys Something, it Belongs to Them.

If a child buys a car in a free-to-play game, it isn’t cool to also make them buy fuel in order to play with it. That’s fine in a game for older players; they understand the caveats that accompany a purchase and can decide what the experience is worth to them. But a child equates that car with a toy, and when you buy a toy, it’s yours to play with — full stop. Look at the things you’re selling in your game as toys, and ask a child what their expectations would be if they bought one.

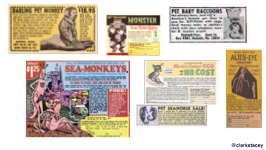

3. Demonstrate Value to Parents (Don’t Sell Sea Monkeys)

These ads led me to expect that for $1.25, I would get a giant bowl of goldfish-sized naked people that could be taught to do tricks when they weren’t working on improvements to their underwater castle. When I ordered them and finally got them to grow, however, I got a plastic cup of brine shrimp: hideous little water cockroaches that science once sent to the moon on one of the Apollo missions to see if space could kill them, which it could not.

Nobody in my circle of friends who ordered Sea Monkeys from comic book ads came away from the experience delighted, feeling like their expectations were met.

“Educational value” seems to be the mobile app equivalent of the illustrations in the Sea Monkeys ad. Not every children’s game or app needs to have an overt educational component, and those that don’t shouldn’t pretend otherwise. Educational content isn’t the only way to demonstrate value to parents. You can make parents glad they downloaded your app by involving them. Provide opportunities for cooperative play with their child, or create experiences that the child will want to tell them about. You don’t want the only parent-child dialogue around your game to be the child asking for money.

4. Don’t Center Your Monetization Around IAP Consumables.

It makes the job of headline writers easy every time a child runs up an eye-popping app store bill by buying food for a virtual pet, or coins to advance a virtual village. News outlets take up their placards and pitchforks denouncing the developer, and occasionally even have a go at the oblivious parents for good measure. It’s great clickbait.

It’s true that developers, parents, and platform operators have a responsibility to govern children’s access to real-money purchasing functionality in apps designed for them. But often the Skinner Box lures that drive these purchases were designed for fishing in the adult F2P ecosystem of whales and minnows, where game design serves the singular purpose of giving big spenders plenty of opportunities to spend big. In that ecosystem, monetization experts tell us, players should never run out of reasons to spend money.

Are consumables always wrong in kids games? That depends both on the target audience, and how you define consumables. At WildWorks we define consumables as game systems that must be recharged each play session to provide access to core play mechanics. We ask ourselves this question: if this was a physical toy, would a child intuitively understand what they’re really getting, and how long it will last? And perhaps most importantly, is there a clearly visible ceiling to what a player can possibly spend in the game, or is that limit a mirage that recedes whenever a player approaches it?

Not all IAP consumables are inappropriate for older children. Kids in the 9-11 year old demographic can grasp some of these value propositions much more easily than younger children. But the most profitable mobile games make adept use of addictive progression loops, loss aversion, and the sunk cost fallacy to keep players spending indefinitely and without limit. These occluded psychological techniques to create whales among adult players have no place in apps for children of any age.

That brings us to the fifth and final principle.

5. Be Transparent.

The toy analogy one last time: if I buy my child a toy that requires batteries, I know to factor that into my assessment of the toy’s value prior to purchase. My child understands that when the batteries are depleted, they’ll have to be replaced or recharged (although in most cases, he can continue playing with the toy regardless).

However, if I buy my child an energy potion so he can reach Level 9 in a F2P game, neither of us know that he’ll need 5 more energy potions to reach Level 10. In fact, the game is designed to deliberately obscure how many purchases he will need to make in order to clear the next level. This violates a visceral, inborn sense of playground fairness; the economics that all children understand because it’s hardwired into the human limbic system.

Clark Stacey

CEO, WildWorks

@clarkstacey